When I was young, a coach was a guy in a t-shirt with a whistle around his neck, instructing and encouraging—often in less than gentle terms—athletes to excel. Today, there are coaches in almost every field—executive coaches, career coaches, instructional coaches, life coaches, health and fitness coaches, and book coaches.

Since I spent most of my career in education, the first type of non-sports coaching I learned about was instructional coaching. During the years I managed a statewide coaching program for elementary school teachers, I read widely in the academic research on coaching, attended training alongside our coaches, and observed them working with teachers in schools.

In his 2011 New Yorker article “Personal Best,” Dr. Atul Gawande wrote about how, when he’d been a surgeon for about eight years, he felt his professional learning curve start to flatten. He wondered what he could do to start improving again, and the idea came to him when he was on vacation and playing tennis with a coach at the resort—he needed a coach for surgery.

Only there was no such thing. So Gawande found one, a retired surgeon he’d trained under during his residency. He paid this doctor to watch him perform surgery, then critique his performance and make suggestions for improvement in a post-op debrief. After he began working with his coach, Gawande’s rate of post-operative complications decreased. His professional learning curve broke its plateau and again started to rise.

“Good coaches,” Gawande writes, “know how to break down performance into its critical individual components.” Those components differ from one field to another, but the generalization is accurate. In book coaching, those components include story structure, characterization, voice, realistic dialogue, conflict, syntax, grammar, and punctuation, as well as strategies for overcoming fear, negative self-talk, procrastination, and other things that keep writers from getting to The End.

In Gawande’s words,

The concept of a coach is slippery. Coaches are not teachers, but they teach. They’re not your boss—in professional tennis, golf, and skating, the athlete hires and fires the coach—but they can be bossy. They don’t even have to be good at the sport. The famous Olympic gymnastics coach Bela Karolyi couldn’t do a split if his life depended on it. Mainly, they observe, they judge, and they guide.

This was true of the book coach I worked with, Jill Angel at Author Accelerator. She hadn’t written—never mind published—a novel. And yet her feedback on mine was spot on. I incorporated most of her suggestions, though not all, since it’s the writer who has the final say on her or his own work, not the coach.

Author Accelerator, the company Jennie Nash founded when her book coaching business became so successful that she needed to bring on other coaches, has become almost synonymous with book coaching, and now offers a certification course for aspiring book coaches.

Not every writer needs a coach—or needs one for the same reason. Writers who, according to Gretchen Rubin’s Four Tendencies Framework, are Obligers need the accountability a coach can provide in order to write their way to The End. Writing groups and critique partners can also provide accountability, but some people will find excuses to skip a group meeting but won’t skip a coaching session they’re paying for.

Accountability isn’t the only reason a writer might hire a coach. According the Four Tendencies, I’m a Questioner, and we don’t need—or even want—external accountability. What I did need was feedback and someone with whom to brainstorm and talk about my writing, as well as the structure that weekly submissions of pages provided. For me, coaching was something I needed while I was building a network of support, which I now have. For other writers, coaching is an ongoing support, part of their regular practice the way it is for athletes.

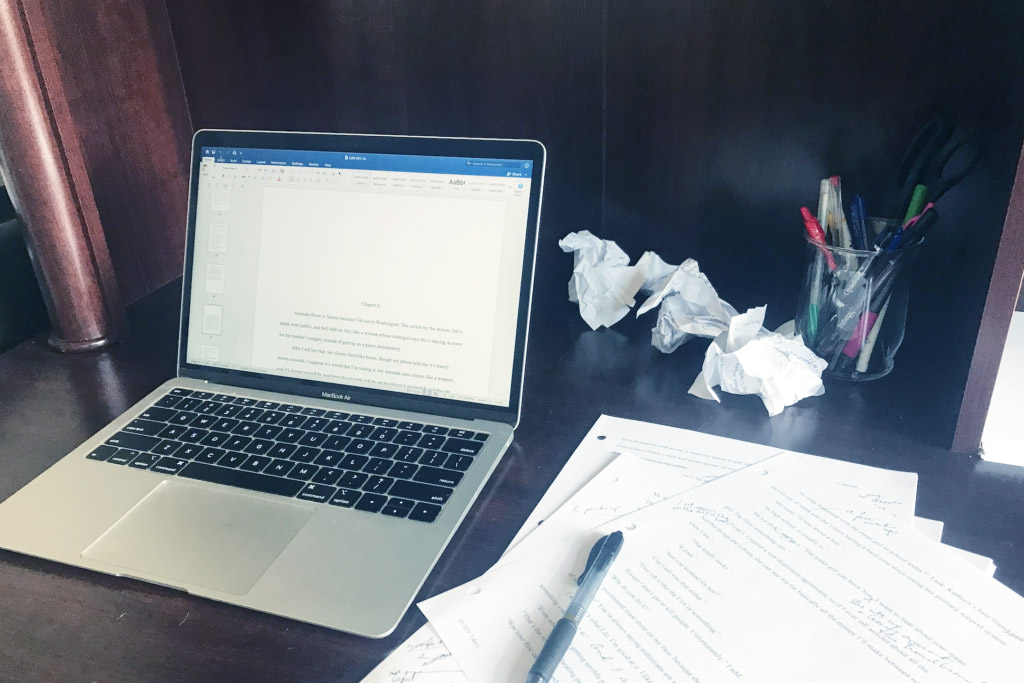

When I was working with a book coach, I would occasionally think, do I really need this? Did Jane Austen need a coach to write Pride and Prejudice? No, but she didn’t need a computer or Microsoft Word or the Internet, either. She also had servants and no kids or career.

Eventually, I stopped worrying about what writers did or didn’t do in the past. We live and write in the age of Scrivener and MacBooks and book coaches. We don’t have to write in isolation any more than we have to write longhand or on a typewriter. If a gymnast or a surgeon can hire a coach to reach their personal best, why shouldn’t a novelist?